This article was written for members of the Intranet Professionals LinkedIn group. But the full text didn't fit there, so I'm publishing it publicly on here instead for any UX nerd to learn something cool.

Hello intranet experts!

I’m making an intranet for a client. We’ve adapted a solidly performing IA from the company's previous intranet.

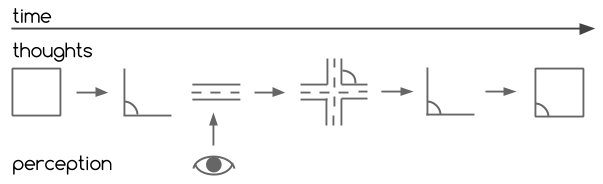

So I’m rebuilding the dynamic main menu that contains the IA. Hover the mouse over the first level section (1LS), and it displays its 2nd level sections (2LS). Hover over one of those, you get a list of 3LSs and articles. Hover over a 3LS and you get a list of its articles. Click article, get info. Familiar right?

This approach means that for a bit of mouse wiggling, ONE click, and ONE page-load, users can navigate to any intranet content. Love it! A worthy Golden Standard for menus.

But In order for this menu to perform intuitively, I’ve got to arrange these 2LSs in the order in which they’re most used. Doing the Product section, for example, the 2LS “Carpet” is first because this company sells more carpet than “Tiles”. More “Tiles” than “Commercial”. More “Commercial” than “Accessories” like curtains and rugs.

Then I think about that last comparison. Yes, Commercial flooring forms a major revenue stream. But! There are more actual transactions in which small products (like rugs and curtains) are sold to customers.

So which should I place higher in this dropdown menu? And there’s the epiphany:

Hello intranet experts!

I’m making an intranet for a client. We’ve adapted a solidly performing IA from the company's previous intranet.

So I’m rebuilding the dynamic main menu that contains the IA. Hover the mouse over the first level section (1LS), and it displays its 2nd level sections (2LS). Hover over one of those, you get a list of 3LSs and articles. Hover over a 3LS and you get a list of its articles. Click article, get info. Familiar right?

This approach means that for a bit of mouse wiggling, ONE click, and ONE page-load, users can navigate to any intranet content. Love it! A worthy Golden Standard for menus.

But In order for this menu to perform intuitively, I’ve got to arrange these 2LSs in the order in which they’re most used. Doing the Product section, for example, the 2LS “Carpet” is first because this company sells more carpet than “Tiles”. More “Tiles” than “Commercial”. More “Commercial” than “Accessories” like curtains and rugs.

Then I think about that last comparison. Yes, Commercial flooring forms a major revenue stream. But! There are more actual transactions in which small products (like rugs and curtains) are sold to customers.

So which should I place higher in this dropdown menu? And there’s the epiphany:

I shouldn’t be sequencing these menus items based on revenue OR sales at all!

I should be sequencing them based on HOW OFTEN my lovely users look up content in these 2LSs. Maybe they need to refer to a table several times per sale for one product — or can sell some products without looking anything up.

Therefore I need to use actual web metrics and user behaviours to determine the right page order, and focus on the question “which content is looked at with the highest frequency?”

This is common sense for you IA pros, but I am one of those too and this very nearly caught me out. So I figured I’d share that with you.

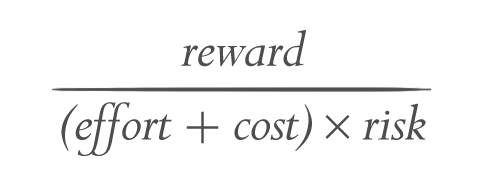

Why do I bother screwing around with these menu to such a tiny degree of detail?

Because the pay off is in micro-movements of the wrist — by not having to move the mouse cursor as many millimetres when navigating in this precise little menu. In tangible terms that stuff adds up to faster work time. Because every client's users deserve a precision solution.

In intangible terms the pay off is in less reading. I’m talking about the psychological aspect of “Why the scrud is this insignificant category higher in the menu the main product category!?”

Avoiding those little moments yields a better user experience. Which can also be measured in knowledge worker satisfaction, and ultimately productivity, ROI, and all those other big quality metrics.

I’d love to hear other IA epiphanies like this if you guys have got them to share. I find the little details of making incredible information-seeking experiences infinitely interesting. :)

Michael

Therefore I need to use actual web metrics and user behaviours to determine the right page order, and focus on the question “which content is looked at with the highest frequency?”

This is common sense for you IA pros, but I am one of those too and this very nearly caught me out. So I figured I’d share that with you.

Why do I bother screwing around with these menu to such a tiny degree of detail?

Because the pay off is in micro-movements of the wrist — by not having to move the mouse cursor as many millimetres when navigating in this precise little menu. In tangible terms that stuff adds up to faster work time. Because every client's users deserve a precision solution.

In intangible terms the pay off is in less reading. I’m talking about the psychological aspect of “Why the scrud is this insignificant category higher in the menu the main product category!?”

Avoiding those little moments yields a better user experience. Which can also be measured in knowledge worker satisfaction, and ultimately productivity, ROI, and all those other big quality metrics.

I’d love to hear other IA epiphanies like this if you guys have got them to share. I find the little details of making incredible information-seeking experiences infinitely interesting. :)

Michael

RSS Feed

RSS Feed