Introduction

Before taking an action, our brain evaluates the merit of that action. Normally this happens in microseconds! But it can be prolonged, sometimes indefinitely. But before we take an action we hit it with an evaluation by comparing the reward with the effort required. Only actions with a sufficiently high reward-to-effort ratio actually get done. If the ratio is too low, we simply will not take action. Even those "I didn't think, I just acted" moments are premeditated — any action must always be thought of before it can be performed. And by thinking of the action we consider our motivation for doing it, which means imagining a reward resulting from it. This is true for every human action except those occurring reflexively or automatically at the physiological level: like convulsions of the skeletal muscle upon being electrocuted, breathing, or heart beat.

As a species, our judgement couldn't be considered "foolproof" by any measure. In fact there are thousands of foolish actions undertaken by humans every day, all of them somehow getting past a legitimate evaluation process of their reward and effort. Our judgement just isn’t perfect.

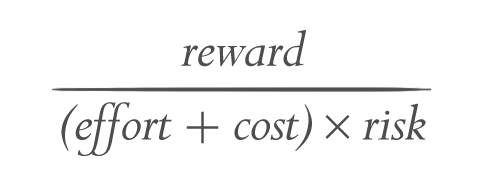

Even though we evaluate actions before taking them, we don't use consistent metrics in our decision making. But what we do have is a consistent process. The equation below describes that process in a formula.

As a species, our judgement couldn't be considered "foolproof" by any measure. In fact there are thousands of foolish actions undertaken by humans every day, all of them somehow getting past a legitimate evaluation process of their reward and effort. Our judgement just isn’t perfect.

Even though we evaluate actions before taking them, we don't use consistent metrics in our decision making. But what we do have is a consistent process. The equation below describes that process in a formula.

The Human Decisioning Equation

The four major components of the formula are detailed below.

1. Reward is the behaviour motivator, and what the ratio is all about. A reward is by definition an improvement of an individual's circumstances. It can be the attainment of something desired (like money, status, recognition, an experience — anything that we know will evoke a positive emotional response in us). A reward is no less of a reward if it does nothing more than improve our circumstances from bad to less bad. So long as we know it will carry a positive emotional reaction it's a reward, and can therefore be evaluated using the ratio.

2. The Reward forms half the equation, and is weighed against the Effort, Cost, and Risk of pursuing it to determine if action will be taken. If the Effort/Cost/Risk are perceived to be too great, the evaluated action is not taken:

3. Measuring reward can sometimes be done in a tangible way: a monetary reward can be measured in dollars. But sometimes the reward is nothing more than a feeling, and measuring emotions is more difficult. For ease of use in this explanation we'll use a simple 1-10 scale for measuring emotional significance.

2. The Reward forms half the equation, and is weighed against the Effort, Cost, and Risk of pursuing it to determine if action will be taken. If the Effort/Cost/Risk are perceived to be too great, the evaluated action is not taken:

3. Measuring reward can sometimes be done in a tangible way: a monetary reward can be measured in dollars. But sometimes the reward is nothing more than a feeling, and measuring emotions is more difficult. For ease of use in this explanation we'll use a simple 1-10 scale for measuring emotional significance.

1. Effort is no more than the physical and cognitive work required to gain the reward.

2. Effort evaluation is a key factor in decision making, because it requires that we determine what actions are required and how time consuming and difficult they'll be to perform.

3. Effort is measured by two metrics: duration of effort (time expenditure) and difficulty of effort (derived from complexity). If the physical effort is immense (e.g. climbing to the top of Mt Everest) it could outweigh the reward all by itself -- without the need to even consider cost or risk. Likewise if the cognitive effort is immense (e.g. learning the set of skills required to cut, shape, and weld steel) the effort could outweigh the reward. In our simple numeric scale of measure, effort is rated 1-10: 1 being minimal, trivial effort; 10 being the maximum effort we could consider taking for a reward.

2. Effort evaluation is a key factor in decision making, because it requires that we determine what actions are required and how time consuming and difficult they'll be to perform.

3. Effort is measured by two metrics: duration of effort (time expenditure) and difficulty of effort (derived from complexity). If the physical effort is immense (e.g. climbing to the top of Mt Everest) it could outweigh the reward all by itself -- without the need to even consider cost or risk. Likewise if the cognitive effort is immense (e.g. learning the set of skills required to cut, shape, and weld steel) the effort could outweigh the reward. In our simple numeric scale of measure, effort is rated 1-10: 1 being minimal, trivial effort; 10 being the maximum effort we could consider taking for a reward.

1. Cost is any expense that will be incurred by taking the actions required for the reward. In many cases this is monetary, but it applies to any resource expense (except time, which is addressed in the evaluation of effort).

2. Cost matters to the equation because it factors in any element of loss to the decision. When there is a reward to be gained, the cost determines its price.

3. We measure cost tangibly where possible: money out, resources traded or consumed (which can be converted to a monetary figure). But cost can also be intangible -- in some cases there's an emotional cost involved when taking an action, or even a psychological cost if the action is potentially traumatising. Most decisions in life are minor, and cost can usually be be most usefully defined as a simple dollar value: preferably $0.

4. The significance of cost is relative to the context, so a dollar figure alone is inadequate for the decision. By cost being contextual, I mean that $100 is a very high cost for a pizza: perhaps a prohibitively high cost rating like 10/10 on the cost scale. But $100 is a very good deal on the latest GoPro, and which we might call a cost rating as a 2/10 in that context, despite the amount of money being exactly the same. The cost rating is really just a measure of your perceived value, which is why converting it to the 1-10 scale is vital. Doesn’t it seem utterly loopy turning a tangible and quantitative unit of measure (dollars) into an intangible qualitative unit (perceived value)? Sure it does. But it’s necessary in order to analyse the significance of the cost.

2. Cost matters to the equation because it factors in any element of loss to the decision. When there is a reward to be gained, the cost determines its price.

3. We measure cost tangibly where possible: money out, resources traded or consumed (which can be converted to a monetary figure). But cost can also be intangible -- in some cases there's an emotional cost involved when taking an action, or even a psychological cost if the action is potentially traumatising. Most decisions in life are minor, and cost can usually be be most usefully defined as a simple dollar value: preferably $0.

4. The significance of cost is relative to the context, so a dollar figure alone is inadequate for the decision. By cost being contextual, I mean that $100 is a very high cost for a pizza: perhaps a prohibitively high cost rating like 10/10 on the cost scale. But $100 is a very good deal on the latest GoPro, and which we might call a cost rating as a 2/10 in that context, despite the amount of money being exactly the same. The cost rating is really just a measure of your perceived value, which is why converting it to the 1-10 scale is vital. Doesn’t it seem utterly loopy turning a tangible and quantitative unit of measure (dollars) into an intangible qualitative unit (perceived value)? Sure it does. But it’s necessary in order to analyse the significance of the cost.

1. Risk exists when there is a possibility of an undesired outcome. An action taken to gain a reward doesn't always have a single possible outcome: even if I take the action "order the pizza" to attain the reward "sate my hunger" there exists the chance that the order won't be fulfilled, or that I will throw the pizza onto the roof of my home in a spontaneous fit of rage. Either one of those two undesired possibilities robs me of my intended reward. But the most likely outcome is that I'll get a pizza to eat, achieving the desired outcome. So the risk is within an acceptable parameter for the action to be taken. In short, a risk is any chance of an outcome that is not desired.

2. Risk can drop reward attainment right in the toilet, particularly if the subject is afraid of risk. This is significant to the equation because a general fear of risk, or fear of a specific outcome, introduces emotional weight to decision-making, pitting our fear directly against our desire.

3. Once the risks of taking a given action have been considered, and the legitimate risks identified, they need to be evaluated for the likelihood of its occurrence versus the likelihood of the desired outcome.

So here I assign an estimated likelihood to each possible outcome:

99.8% (Desired outcome) I receive a pizza to eat.

0.1% I receive no pizza.

0.1% I receive a pizza but throw it on the roof in anger.

There are any number of potential outcomes to an action of course. Analysis should only include those which are both foreseeable and significant.

In this example I've determined there's very little risk of things not going as planned. Total risk is only 0.2%. Translating this to a simple 1-10 metric, the risk is 0/10: almost certain to yield the desired outcome.

2. Risk can drop reward attainment right in the toilet, particularly if the subject is afraid of risk. This is significant to the equation because a general fear of risk, or fear of a specific outcome, introduces emotional weight to decision-making, pitting our fear directly against our desire.

3. Once the risks of taking a given action have been considered, and the legitimate risks identified, they need to be evaluated for the likelihood of its occurrence versus the likelihood of the desired outcome.

So here I assign an estimated likelihood to each possible outcome:

99.8% (Desired outcome) I receive a pizza to eat.

0.1% I receive no pizza.

0.1% I receive a pizza but throw it on the roof in anger.

There are any number of potential outcomes to an action of course. Analysis should only include those which are both foreseeable and significant.

In this example I've determined there's very little risk of things not going as planned. Total risk is only 0.2%. Translating this to a simple 1-10 metric, the risk is 0/10: almost certain to yield the desired outcome.

Other Factors

These 1-10 ratings are completely subjective in their own right, and only serve to compartmentalise judgement to enable comparative sense to be made. But what can cloud their accuracy?

Acceptance Threshold

The threshold is about how much negative you’re willing to tolerate for the attainment of something positive. It varies from person to person. A threshold too high would mean actions are approved and taken more often than the average person. A threshold too low would mean actions are not approved and taken as often as they are for the average person. The acceptance threshold is not fixed, however: it changes as we develop our judgement and get experience in accurately estimating the difficulty of effort, the significance of cost, and the likelihood of risks.

Underestimation

An effort, cost, or risk could be more significant than you originally thought. It happens, learn from it. Getting hung up on accurate estimates defeats the point of having a numeric decision making system.

Recording in a spreadsheet your estimated R, e, c, an r ratings of various judgements and their actual ratings (determined after the action has been taken) will give you data that'll allow you to see if you tend to over- or underestimate when making decisions. You'll then be able to compensate with data-assisted precision.

Recording in a spreadsheet your estimated R, e, c, an r ratings of various judgements and their actual ratings (determined after the action has been taken) will give you data that'll allow you to see if you tend to over- or underestimate when making decisions. You'll then be able to compensate with data-assisted precision.

Missing Data

If key information is unavailable (e.g. unforeseeable costs, an additional element of risk, or an unanticipated action requiring effort on the part of the subject) then the evaluation process will be imperfect: the optimal logic of the equation alone is insufficient; a complete and accurate data set is required for an optimal decision.

The ratio can become further complicated when the expected emotional value is not a precisely known, but is anticipated to fall in a range, like "between 7 and 9".

But you don't need an optimal decision: that would be pre-determinism in its final state. You just need a decision to act or not. Sometimes things will go right, but every time you have a chance to learn and improve your judgement.

The ratio can become further complicated when the expected emotional value is not a precisely known, but is anticipated to fall in a range, like "between 7 and 9".

But you don't need an optimal decision: that would be pre-determinism in its final state. You just need a decision to act or not. Sometimes things will go right, but every time you have a chance to learn and improve your judgement.

Dishonesty

Not being honest with yourself about the significance of obstacles (effort required, costs, risks) can ruin your judgement.

Confirmation Bias

If we rule out the action on grounds of it being too much effort, too costly, or too risky, our brain often does a completely unobjective behaviour. It flips between the three to build confirmation bias.

Once habitualised, this cognitive phenomenon forms the basis of pessimism. The same phenomenon, but with a focus on the reward or rewards of the action, is the pattern responsible for optimism.

Once habitualised, this cognitive phenomenon forms the basis of pessimism. The same phenomenon, but with a focus on the reward or rewards of the action, is the pattern responsible for optimism.

Emotional Disproportion

There are some simple techniques for counteracting some of the effects of strong emotional influences on decision-making:

- Identify strong emotions — Sometimes simply being aware of how you feel and why is enough to remove the emotional bias.

- Put time between decision-making sessions -- Not all decisions have to be made in the first attempt. Uncertainty can sometimes be conquered by facing the decision later when you're in a calmer state.

- Environmental changes -- Stressors affect the emotional state via perceptions and effects on the physical state. Address these

- Maslow evaluation — Are your basic physical and emotional needs being met? If not, emotions will be intense and severely influenced by this. Satisfy these needs before proceeding with the decision if possible.

And that, learners, is the secret equation that decides everything you do, and a system for formulaically quantifying it.

But it's not always possible to quantify Reward, Effort, Cost, and Risk for every decision we make. In most instances it's worthwhile not to bother measuring it all, since our normal cognition handles the bulk of our decisions almost automatically, microseconds fast, and without the hassle of trying to find a pen. Moreover, the actual metrics of the evaluation system are completely intangible: in many cases it's the expectation that we'll feel a particular feeling that is adequate reward to compel us to spend effort, cost, and accept risk.

In a subsequent blog post we’ll examine The Action Threshold, and provide a tool for recording efficacy data on decision making.

But it's not always possible to quantify Reward, Effort, Cost, and Risk for every decision we make. In most instances it's worthwhile not to bother measuring it all, since our normal cognition handles the bulk of our decisions almost automatically, microseconds fast, and without the hassle of trying to find a pen. Moreover, the actual metrics of the evaluation system are completely intangible: in many cases it's the expectation that we'll feel a particular feeling that is adequate reward to compel us to spend effort, cost, and accept risk.

In a subsequent blog post we’ll examine The Action Threshold, and provide a tool for recording efficacy data on decision making.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed