The following is a conceptual model explaining the formation of opinion, belief, and conviction.

Opinions

Opinions are thoughts validated by multiple observations and second hand evidence. They're formed simply by exposure to perceived evidence, regardless of evidence quality. Fortunately they are easily discarded or modified when more credible contrary evidence becomes available upon which to base a more informed opinion.

Beliefs

Beliefs are the intermediate step between opinions and convictions. A belief forms when a sufficient quantity of evidence is amassed to justify exchanging memory-retained evidence for a strong feeling of certainty. We form beliefs to reduce cognitive load and free our attention for new thoughts. To form a belief, we remove the many thoughts that form the evidence for that belief from our thought cycle (because it's cognitively expensive to retain all that information when we can just hold onto the conclusion that all that evidence points to). We replace all that evidence information with only the conclusion itself: this is a belief. We also retain an emotional weighting of our surety of that conclusion, proportionate to the evidence we used to form it. By doing so, we free our thought cycle for new thoughts without losing the most important information obtained from the process of learning by storing that high-value thought as a belief. In short, a belief is an opinion where we've disposed of the supporting evidence and filled that space with a strong feeling of surety.

Beliefs are harder to change than opinions, because in order to do so we have to pit new evidence against our strong feelings! This is difficult, cognitively expensive, and often we double-down on our feelings and simply get angry instead of evaluating the evidence. (My hypothesis is that it's often neurologically easier to intensify an emotion than it is to evaluate evidence contrary to an existing belief.)

Beliefs are harder to change than opinions, because in order to do so we have to pit new evidence against our strong feelings! This is difficult, cognitively expensive, and often we double-down on our feelings and simply get angry instead of evaluating the evidence. (My hypothesis is that it's often neurologically easier to intensify an emotion than it is to evaluate evidence contrary to an existing belief.)

Convictions

Convictions are thoughts reenforced by strong feelings of not sure surety but certainty. A conviction is an idea that has been accepted absolutely, by a person who has made the decision to entertain no evidence contrary to the conviction. Discourse challenging the conviction will, rather than prompt thought and re-evaluation of the evidence on which the conviction is based -- which at this point is often prohibitively difficult due to the abandonment of the thoughts forming the evidence -- and will instead become an emotional matter, in which the emotional weight of the conviction is weighed against he new evidence which will then be dismissed if it carries insufficient emotional weight of its own.

Whenever we share our convictions we usually state them as if they're facts, which we are convinced that they are, since they're something we have learned. When others ask for evidence to support our claims of factuality we sometimes can't deliver and simply respond with "because it just is," with a sense of exasperation.

Thats the cost of the exchange that occurs when beliefs mature into convictions. But the benefit of the exchange is that it frees our thought cycle for new observations, new thoughts, and new evidence on which we can form new beliefs and thereby continue learning.

This is why its easier for us to form new beliefs than change our existing ones; we cant easily recall and reevaluate all the old evidence we've put out of circulation.

Whenever we share our convictions we usually state them as if they're facts, which we are convinced that they are, since they're something we have learned. When others ask for evidence to support our claims of factuality we sometimes can't deliver and simply respond with "because it just is," with a sense of exasperation.

Thats the cost of the exchange that occurs when beliefs mature into convictions. But the benefit of the exchange is that it frees our thought cycle for new observations, new thoughts, and new evidence on which we can form new beliefs and thereby continue learning.

This is why its easier for us to form new beliefs than change our existing ones; we cant easily recall and reevaluate all the old evidence we've put out of circulation.

Thought Cycle

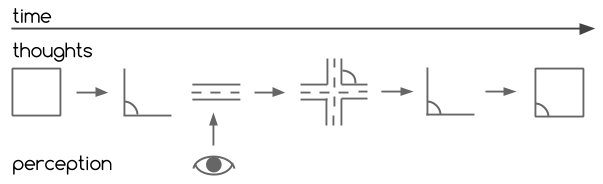

Thought cycling is the repetition of thoughts through attention. An example is illustrated:

The train of thought starts off thinking about squares. The thought vector (which could go in any direction, to literally any other thought!) happens to move to thinking about right angles. Next, a perception: the brain sees a road. It starts thinking about roads. Thought vector progresses to thinking about the angles between intersecting roads. Then a thought vector goes back to thinking about right angles. And lastly a vector moves on to thinking about the angles of squares (a very similar thought to the first thought in the train, but not exactly the same).

In this train of thought (i.e. sequence of thoughts), the "thought cycle" is described thus:

Notice how much data is generated from just 6 sequential thoughts! Now consider that our day-to-day trains of thought are far more complex than this. They're non-stop! Trains of thought tens of thousands of thoughts long that generally include everything from the right amount of toothpaste to use, to what other people think of the way you look, to the state of the economy. The thoughts we cycle change in frequency according to our interests, our perceptions, and the direction of our attention.

Since thoughts derive beliefs, and our beliefs determine our behaviour, it's wise to have an awareness of our own thoughts. And from time to time ask ourselves the question: "What is the most valuable thought I could think?"

In this train of thought (i.e. sequence of thoughts), the "thought cycle" is described thus:

- 1 recurring thought ("right angles")

- One perceptual input ("roads")

- 5 internally derived thoughts ("squares", "right angles", "angles of roads", "right angles", "angles of squares")

- 4 thought vector progressions between related thoughts

- 2 cross-referenced thoughts ("angles of roads", "angles of squares")

- 16.% (1 in 6) of thoughts were cycled in the train of thought twice, meaning it was "cycled" in the train of thought.

Notice how much data is generated from just 6 sequential thoughts! Now consider that our day-to-day trains of thought are far more complex than this. They're non-stop! Trains of thought tens of thousands of thoughts long that generally include everything from the right amount of toothpaste to use, to what other people think of the way you look, to the state of the economy. The thoughts we cycle change in frequency according to our interests, our perceptions, and the direction of our attention.

Since thoughts derive beliefs, and our beliefs determine our behaviour, it's wise to have an awareness of our own thoughts. And from time to time ask ourselves the question: "What is the most valuable thought I could think?"

RSS Feed

RSS Feed