Humans love labels. We use labels to categorise our world and all the things in it. They're a simple, one-datum way of assigning any number of attributes to a subject. Our brains can assign labels by the trillion and still not only have room but hunger for more! Labels can be hurtful, like "blaggard" or "buttmachine". They can be winsome, like "beauty", or "champion". They can be fundamental, like "good", and "right". They identify us: "writer", "father". They can be given away freely, and received without asking. They can be wanted, or reviled. They can and will stick to anything -- just not in all cases.

| The worldly uncle of the Label is the Spectrum. Spectra bring sophistication to your analysis. They help us understand subjects in the context of any combination of attributes. For example I can take the spectrum of emotion intensity and the double-spectrum of certainty and make a graph encompassing the entire remit of human attitudes toward divinity. |

I find this type of thinking is incredibly useful for generating insight. On the aforementioned spectrum, once I place you upon it, or you place me upon it, we have significant insight into each other's worldview. And how do we place each other on such a spectrum? With labels like "Hindu", "atheist", "Christian", "zealot", "infidel", "agnostic", or "ignoramus". The degree to which we agree with the labels others determines our reactions, generating yet more information. This is some crazy-powerful insight to glean into one another given the fact that all it takes to obtain it is to create a perspective-gaining spectrum from two simpler ones, and obtaining two happy little datums from someone with regard to the topic: in this example their nature of their beliefs regarding the Divinity Question on a scale of -10 to 10 and the intensity of that belief on a scale of 1 to 10. Not into pigeon-holing folks over their religious views? Good for you! There is a whole world of spectrums upon which to ponder the things that do interest you... and I have no doubt that you are phenomenal at it!

So we can see that spectrums are useful for framing new perspectives and obtaining labels. Labels themselves are useful for effortlessly producing literal terabytes of synaptic data reservoirs in our brains to form and store knowledge of the things we trouble ourselves to learn about.

Despite all this, people who coin new labels are often forgotten to history. You yourself probably know well over 30,000 labels in your native language, and yet how many of them can you trace etymologically back to first usage? Bugger all, that's how many. And why? Because the makers of labels don't really have a defining label in common other than "labeller", and that label applies to us all. Don't feel the least bit bad about that, it's human nature.

But if labels are so useful, why do I have a bone to pick with the practice of labelling? It's because, since labelling is such a force of (our own) nature, its power can be misused. I'm not just talking about the time Mrs Simmers labelled you a "mouth-breather" in front of the whole class. I'm talking about when our lazy brains generate extra labels to do the job that should belong to the noble spectrum. When this happens, it causes us to frame our perceptions in terms of "this or that" instead of "this on a scale of 1 to 10, times that on a scale of 1 to 10".

The phenomenon has many names and many forms: Laziness. Narrow-mindedness. Simplemindedness. Bigotry. A very common, all-inclusive description is "to see things in black and white."

A rather important instance of label over-reliance is in the modern taxonomical classification of species.

Despite all this, people who coin new labels are often forgotten to history. You yourself probably know well over 30,000 labels in your native language, and yet how many of them can you trace etymologically back to first usage? Bugger all, that's how many. And why? Because the makers of labels don't really have a defining label in common other than "labeller", and that label applies to us all. Don't feel the least bit bad about that, it's human nature.

But if labels are so useful, why do I have a bone to pick with the practice of labelling? It's because, since labelling is such a force of (our own) nature, its power can be misused. I'm not just talking about the time Mrs Simmers labelled you a "mouth-breather" in front of the whole class. I'm talking about when our lazy brains generate extra labels to do the job that should belong to the noble spectrum. When this happens, it causes us to frame our perceptions in terms of "this or that" instead of "this on a scale of 1 to 10, times that on a scale of 1 to 10".

The phenomenon has many names and many forms: Laziness. Narrow-mindedness. Simplemindedness. Bigotry. A very common, all-inclusive description is "to see things in black and white."

A rather important instance of label over-reliance is in the modern taxonomical classification of species.

Taxonomical classification's honourable discharge

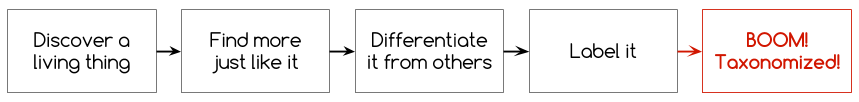

One of the label-based systems of classification in science arose with an originally legitimate purpose: taxonomy. The whole idea began as a way for early humans to tell different types of creature apart and give them labels so they could be discussed simply and easily.

- The ancient Greeks got pretty good at this. So good that even today their method is still considered scientific.

- But a Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus took it to the next level. This fellow founded modern taxonomy in 1700 with his work Institutiones Rei Herbariae, in which he classified about 9,000 species across almost 700 genera. It's from Linnaeus that our modern taxonomical system is derived.

- Humans were able to apply this process of categorisation to extinct plants animals too. ("Hey, let's call this big fella Tyrannosaurus Rex. Boom! Taxonomized!)

- The process was also applied to label species that "link" other species. (It was right here that someone should have realised that labels weren't going to provide a suitable classification system forever.)

- It was in 1968 that the process got freaking super-charged by DNA-sequencing. Thanks to a north American scientist named Bob Holley, the old modus of taxonomical classification -- really diligent systematic labelling -- should have begun to be phased over into a branch-spectrum system of understanding the abundance of life forms we get down here on Earth.

With the fact of gene-mapping now being a thing, we must actually define the genetic limits (they don't even have to be linear limits, since in reality every individual creature simply forms part of an even more granular branching mechanism than is represented by species) that the label "duck" encompasses, for example. In doing this, it's time to admit that taxonomical labels are arbitrary in the extreme. As labels they're still incredibly and irreplaceably useful for talking and learning about ducks; we simply need to progress from using labels to classify beings on what is actually a very real and increasingly understood spectrum of genetic adaptation that encompasses all "species" regardless of whether they're currently known or not.

So the next time you hear the taxonomical label of a species of plant or animal bandied about casually in conversation, give a little thought as to where the limit of that label starts and ends in its evolutionary sequence, and entertain the merit of a system of understanding creatures mathematically, based on their unique genetic link the convoluted branching chain that describes all the life that ever lived and ever will live upon this lovely little planet we call home.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed