Do societies think? Yes, they do. But not like organisms do. Societies think through their component members. A society's facsimile of "thought" is the sum of its members aspirations and beneficence minus their damage. Society maintains its own set of values that, interestingly, are not purely the sum of its component members' values.

One of the key similarities your own society has to you as an individual member and component of it, is that it wants to survive as much as you do. Right up to the point that it would willingly sacrifice you if doing so meant its continued existence, just as you would most likely sacrifice your society (by disbanding its organisation, not culling its populace!) if doing so meant your own survival.

That's a dark thought.

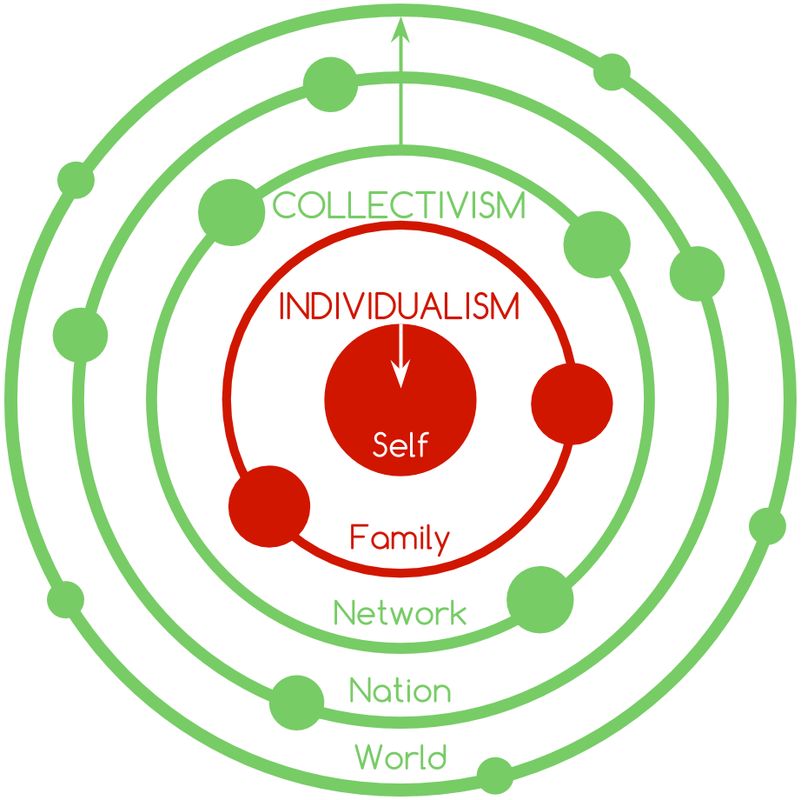

But you and your society, of course, are not enemies. You're more like family (and from society's somewhat creepier viewpoint, you share a body). You also share the goal of seeking prosperity, with the knowledge that the prosperity of the individual and the of society directly affect each other. So how can you be a better member of your society? You can start by expanding your range of atomic perspective, and learning how to think socio-centrically with the same deftness as you can think individualistically. And you can follow all that up by making choices based on that improved perspective.

One of the key similarities your own society has to you as an individual member and component of it, is that it wants to survive as much as you do. Right up to the point that it would willingly sacrifice you if doing so meant its continued existence, just as you would most likely sacrifice your society (by disbanding its organisation, not culling its populace!) if doing so meant your own survival.

That's a dark thought.

But you and your society, of course, are not enemies. You're more like family (and from society's somewhat creepier viewpoint, you share a body). You also share the goal of seeking prosperity, with the knowledge that the prosperity of the individual and the of society directly affect each other. So how can you be a better member of your society? You can start by expanding your range of atomic perspective, and learning how to think socio-centrically with the same deftness as you can think individualistically. And you can follow all that up by making choices based on that improved perspective.

| What does society want? Society's goals (assuming it is a healthy one) are these, in this order:

1. SurvivalSurvival is self explanatory. For a society it's not about being the fittest, since society's don't necessarily compete. The common analogy is that societies, as a type of organisation of organic bodies, are a kind of organism themselves. If that idea helps you gain perspective, then keep it. The point is, society wants to live, and will take whatever steps are necessary to avoid perishing. This is a currently unavoidable artefact of human development, and as long as there are humans they will form societies that have attributes reflecting aspects of human nature. central to these is the will to survive. |

2. Prosperity

This is exactly what it sounds like. Society wants to have an abundance of everything it needs so that it can grow, keep its populace happy and healthy, and just generally enjoy the good life. To achieve this, society needs us to do well. To do well as individuals, it helps if society as a whole is doing well too.

3. Optimisation

Once a society is prosperous, it's only interest is in becoming more so, and not losing the prosperity it has. As such, the goal becomes optimisation. The ideal state where every resource it can incorporate into itself is employed in the most efficient way possible to serve its populace to enable its populace to serve it. We would call this utopia. Some would call this impossible. Some, inevitable. Regardless, the pursuit of utopia is shared by every society that ever was and ever will be.

So why hasn't Societal Optimisation ever been achieved?

The answer seems to be because of the common (and understandable) phenomenon of human individualism. Humans are famously only in it for themselves, instead of in it for themselves and everyone else too. The fundamental human drive to compete rather than collaborate explains this. The trait is best characterised by the Prisoner's Dilemma.

"Rational" behaviour, in this logic game, is typified as purely self-interest motivated behaviour. Contrary to this, the socio-centric viewpoint is that "Rational" behaviour is choosing the behaviour "that harms society the least as a whole". From this actual definition of "rational" behaviour, both prisoners (where they are members of the same society) would always opt to cooperate and to trust each other, thus guaranteeing not only an alleviated sentence for both individuals but the best possible outcome overall. To a society, or a person capable of socio-centric thought, this is the simplest of logic, and serves society's goal of optimisation in which every individual prospers to the greatest degree of prosperity possible. But do humans do this? They do not. The reason why, given the intrinsic value of any healthy society to any human that has ever been a part of one, remains constant: an inherent overvaluation of individualism. The reason for that overvaluation, of course, is simply a combination of a predisposition to the individualistic perspective, and habit.

What will happen if you start thinking like a society? What will happen if you make The Choice?

What will happen is that you'll miss out.

When you make The Choice you will miss out on things you would have gained had you taken the strictly individualistic approach. Right now your human brain is in the process of an evolution that favours immediate term gains over long-term ones, and the first few times you make The Choice to put the holistic benefit of society before the immediate of just you, you will be keenly aware of what you lose out on. It could be that you withdraw a job application because you happen to know that another applicant will do a better job or simply enjoy the work more than you would. It could be that you help a worker struggling to unload a pallet on your way to an appointment causing you to arrive late. It could be that you let someone change lanes in front of you at the expense of several seconds delay because you know it to be most optimal maneuover for the flow of traffic. If and when you do it, it will feel bad for you as an individual. But without The Choice being made within society at all people get prevented from doing the work that they're best at, overburdened labourers develop chronic spine injuries, and motorways get backed up for kilometres every day. Society, and therefore it's component members, do not prosper without some members making The Choice.

And yet when everyone makes The Choice, society survives, prospers, and stands a good chance of becoming optimised. Utopia, therefore, is ultimately a choice that you get to make.

The answer seems to be because of the common (and understandable) phenomenon of human individualism. Humans are famously only in it for themselves, instead of in it for themselves and everyone else too. The fundamental human drive to compete rather than collaborate explains this. The trait is best characterised by the Prisoner's Dilemma.

"Rational" behaviour, in this logic game, is typified as purely self-interest motivated behaviour. Contrary to this, the socio-centric viewpoint is that "Rational" behaviour is choosing the behaviour "that harms society the least as a whole". From this actual definition of "rational" behaviour, both prisoners (where they are members of the same society) would always opt to cooperate and to trust each other, thus guaranteeing not only an alleviated sentence for both individuals but the best possible outcome overall. To a society, or a person capable of socio-centric thought, this is the simplest of logic, and serves society's goal of optimisation in which every individual prospers to the greatest degree of prosperity possible. But do humans do this? They do not. The reason why, given the intrinsic value of any healthy society to any human that has ever been a part of one, remains constant: an inherent overvaluation of individualism. The reason for that overvaluation, of course, is simply a combination of a predisposition to the individualistic perspective, and habit.

What will happen if you start thinking like a society? What will happen if you make The Choice?

What will happen is that you'll miss out.

When you make The Choice you will miss out on things you would have gained had you taken the strictly individualistic approach. Right now your human brain is in the process of an evolution that favours immediate term gains over long-term ones, and the first few times you make The Choice to put the holistic benefit of society before the immediate of just you, you will be keenly aware of what you lose out on. It could be that you withdraw a job application because you happen to know that another applicant will do a better job or simply enjoy the work more than you would. It could be that you help a worker struggling to unload a pallet on your way to an appointment causing you to arrive late. It could be that you let someone change lanes in front of you at the expense of several seconds delay because you know it to be most optimal maneuover for the flow of traffic. If and when you do it, it will feel bad for you as an individual. But without The Choice being made within society at all people get prevented from doing the work that they're best at, overburdened labourers develop chronic spine injuries, and motorways get backed up for kilometres every day. Society, and therefore it's component members, do not prosper without some members making The Choice.

And yet when everyone makes The Choice, society survives, prospers, and stands a good chance of becoming optimised. Utopia, therefore, is ultimately a choice that you get to make.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed